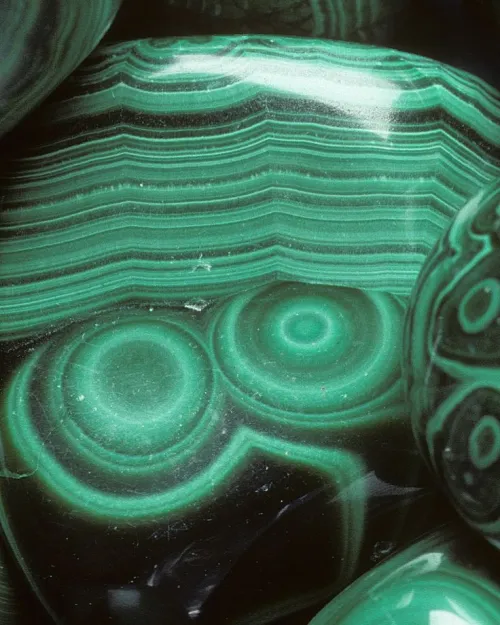

Malachite forms through the chemical weathering of copper deposits when water interacts with copper sulfide minerals, creating the vibrant green bands we recognize; if you remember one thing, it's that this vivid pattern is nature's fingerprint of this transformation process.

Imagine strolling through a gem show with friends when that brilliant green stone grabs your attention. "Is it natural or dyed?" someone asks. Nearby, another visitor debates durability: "Would it crack if worn daily?" These aren't theoretical questions—they're the exact whispers floating around specimens like this one. Conflicting ideas about malachite swirl everywhere: craft blogs oversimplifying its formation, friends questioning durability, even stories about "healing crystals" muddying scientific facts. Sorting these claims can get dizzying. Today, we'll unpack seven core questions about malachite's origins and characteristics, separating romanticized tales from actual geology. Equipped with these insights, you'll confidently evaluate any malachite piece—whether displayed in a gallery or resting in your palm.

Picture browsing a mineral exhibition where a vendor explains, "Malachite just crystallizes from hot magma." That oversimplification sticks because it matches how many gemstones form. This notion persists at markets and galleries where time-pressed dealers skip geological nuance. Technically speaking, malachite forms as a secondary mineral through the chemical weathering of copper sulfide deposits when water, carbon dioxide, and oxygen chemically react with primary copper minerals. The process tends to occur in the oxidized zones of copper-bearing ore deposits over centuries. As you admire pieces in workshops or museums, notice how concentrated greens often align with mineral seams. This visual cue signals copper-rich solutions slowly deposited bandings in rock cavities.

A shopper once argued, "It’s pure copper, so it must be toxic!" This assumption brews because marketing emphasizes copper content without context. Such ideas surface when vendors vaguely reference "natural materials" while sidestepping chemistry. Chemical composition remains copper carbonate hydroxide (Cu₂CO₃(OH)₂), with distinct green hues emerging from varying concentrations of copper ions during formation. The clearer way to see it is this compound forms only through weathering reactions involving CO₂ and water with copper-rich minerals. Sulfuric acid solutions contacting limestone may accelerate precipitation. When examining specimens or jewelry certificates, look beyond "untreated" labels; probe whether bandings show natural irregularities rather than uniform coloring.

Imagine unboxing online-ordered malachite earrings where concentric rings look unnaturally vivid. Comments like "Dye enhances those patterns" often surface because high-gloss photos obscure natural features. People question authenticity since bands appear mathematically perfect in marketing images. What gets missed? Visual banding patterns reflect cyclic mineral precipitation in cavities, while physical characteristics like the 3.5—4 Mohs hardness indicate moderate scratch resistance. Specimens appear opaque with vitreous luster, and density variations between 3.75—4.05 g/cm³ contribute to substantial texture. When handling pieces in stores, test for temperature—authentic malachite may take longer to warm in hand than plastics. True botryoidal forms feel weighty rather than artificially layered.

A gallery visitor once said, "Malachite needs volcanic heat like diamonds." Many confuse formation with lava-born gems because geology feels abstract without visible water features. Why does this persist? Tourist-mine brochures simplify processes, skipping how water flow creates banded color gradients. Reality unfolds when carbon dioxide-rich percolating rainwater infiltrates copper deposits, transforming minerals at ambient to moderately warm temperatures. It primarily develops in oxidized zones requiring oxygen and water exposure over geological time. Picture hiking near copper-rich rocks after rain—while you won’t see real-time formation, fractured rocks and blue-green stains hint at these chemical reactions. When evaluating mine claims, check if locations have seasonal water flow supporting mineral deposition.

Rockhounding or shopping becomes richer when you imagine nature’s workshop: dripping water depositing microscopic layers like time-lapse photography

"Only deep mines yield real malachite," a collector stated at a gem society meeting. This surfaces when documentaries focus solely on industrial copper mines, ignoring secondary formations. Sources vary widely: alongside azurite in Zambia’s oxidized zones, inside Russian Ural Mountain cavities, within Congo riverbeds as weathered fragments. Common geological occurrences see malachite alongside minerals like calcite and chrysocolla in copper mines or surface-level carbonate zones. While admiring raw specimens at natural history museums, observe how angular breaks suggest proximity to primary ore bodies, whereas rounded edges may indicate river transport. Prospecting enthusiasts should note acidic soil conditions near copper indicators like azurite streaks for possible surface deposits.

Attending a jewelry workshop, two creators debated malachite rings: "It lasts forever like quartz!" countered by "It’ll shatter spontaneously!" Such extremes miss nuanced truths. Daily handling concerns originate from Mohs scale readings suggesting fragility. Ornamental objects display striking greens but can be brittle under mechanical stress and require careful cutting to prevent fractures. Long-term value considerations include color saturation, pattern uniqueness, and specimen size—deeper tones and intricate bands may enhance retention. Surface patina can develop over prolonged air exposure. When examining pieces at craft fairs, compare polish quality on banded versus solid patches; varying textures signal authentic carving techniques. Gentle cleaning is advisable.

"Ethically sourced malachite barely exists now," someone claimed during a sustainability panel. Absolutes like this spark when eco-discussions overlook geological timelines. Mining communities balance extraction with economic needs—some Zambian cooperatives restore land while extracting oxidized zone specimens. Others prioritize reducing subsurface blasting since malachite forms near surfaces. Future sourcing may favor weathered deposits requiring minimal excavation. Next time you browse "eco-friendly" stones, ask vendors about extraction depth and land rehabilitation. Does sourcing documentation mention surface collection or shallow pits? Natural patterns can indicate whether material originated near water tables versus deep mines.

Back in that gem show scenario, you’d now see beyond surface beauty: banding patterns whispering of ancient water cycles, weight hinting at carbonate density, color gradients reflecting copper concentrations. Before your next purchase or museum visit, recall that how the stone sits in light reveals its origin story—opaque sections suggest deep formation while surface lustre echoes environmental exposure. If you encounter claims about volcanic origins or everlasting durability, cross-verify with these tangible features. Could this help explain puzzling variations in similar-looking pieces? When the sales clerk gestures toward glowing displays, you’ll know exactly which questions illuminate truth.

Q: Does malachite contain hazardous copper levels?

While composed of copper carbonate, handling polished items poses minimal risks—just avoid inhaling dust during carving or ingesting particles. Soluble copper may release from unsealed raw specimens in acidic solutions.

Q: Why do some malachites show blue specks?

Blue patches can indicate azurite presence since both minerals form in similar environments through copper carbonate reactions, creating striking natural combinations when precipitation conditions vary.

Q: Can I wear malachite rings daily?

Daily wear requires protective settings since malachite may scratch from abrasion and tends to develop surface patina over time, particularly avoiding impacts against ceramics or stones.